Communion

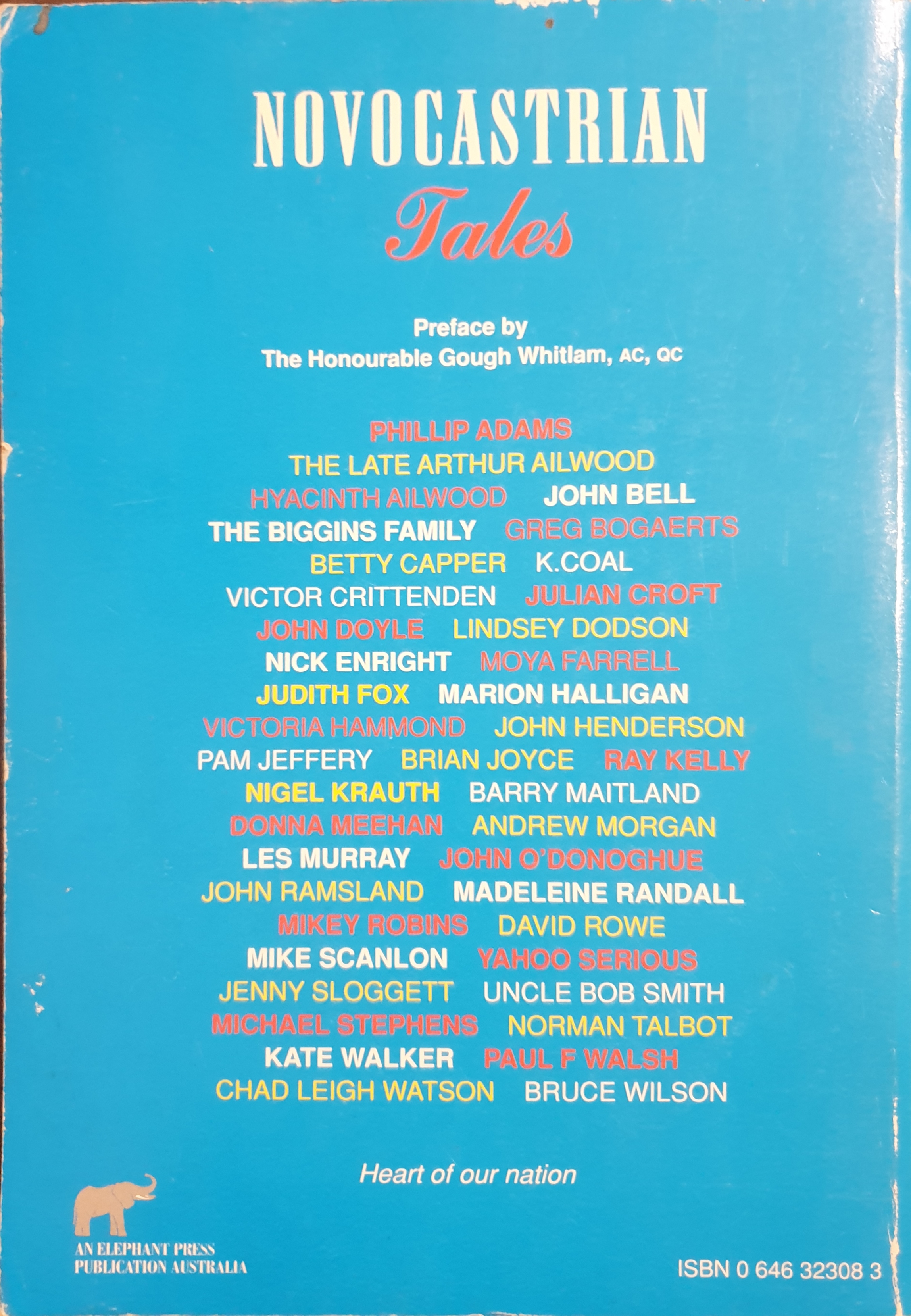

Paul F Walsh

He had been watching me from a distance for some time.

Silent.

Still.

Wary.

Ever vigilant.

His approach was slow and sinuous.

Stalking.

Ever closer.

Silent.

Still.

Wary.

And then he was standing beside me, looking down at my seated figure.

Silent.

Still.

Wary.

Curious.

He touched me on the shoulder.

‘Cambai,’ he said, ‘cambai.’

I later learned that ‘cambai’ meant brother.

‘Me’, he said, ‘me Wepohng!’

He had a smattering of English words.

He was perhaps twelve years old.

‘Me Browne,’ I said.

And then there was silence.

He sat beside me as I tried to capture a preliminary sketch of the view below.

He was as much a part of this world as the stone on which we were sitting.

I had avoided the circle of stones nearby due to his earlier warning gestures.

Everything had meaning here for these blacks.

Hidden meaning.

This boy could see what I could not.

Some stones were said to be sacred in Ireland too.

But I was no Druid.

I was an Irishman of my time.

And I was a world away from Ireland on that 1st.January.1812. day.

‘What that?’ the boy asked.

He was such an innocent, so full of naïve curiosity for a foreign tongue.

I knew what it was to be an outcast in my own land.

And now I was an outcast in his land.

A convict.

I felt an affinity with the plight of these local blacks.

‘What that?’ he repeated, pointing to a tiny creature sunning itself on our shared stone.

‘A lizard,’ I said.

‘Liz … ard,’ he parroted, slowly articulating each syllable.

And then he said something utterly unintelligible to my ear, pointing at the tiny beast, once again sounding each syllable quite distinctly.

‘Coa … tung … ull … e,’ he said.

And I suddenly realised that he wanted me to repeat what he had said in his tongue.

I hesitated, but I eventually uttered what I took to be the word for lizard in blackfella language, and he laughed and laughed at my poor parroting.

‘Liz … ard,’ he repeated again.

I really wanted to communicate with him beyond the barrier of language, so I did a quick sketch of the lizard on the side of my draft sketch of the view from Prospect Hill.

The truth is that I was trained in Ireland to draw such tiny creatures from nature, so my quick rendering of the lizard was of a finer quality than my draft sketch.

The boy watched in wonder as the lizard appeared on the page.

He kept looking at the real lizard on the rock, and then back at my drawing of the lizard, over and over again, and then, bizarrely, he kept looking at my face, and back at the real lizard on the rock, over and over again.

‘Me’, he eventually said, reaching for my pencil.

To my amazement, the boy emulated the manner in which I held the pencil, a unique artisan grip that I had learned in Dublin, and then he leaned towards the sketch and confidently left his mark.

‘You,’ he laughed, ‘liz … ard!’

I could see that he had affixed a rendering of my rather fulsome beard onto the lizard’s face in my quick reptilian sketch.

‘You liz … ard!’ he repeated, laughing and laughing, and then he handed the pencil back to me.

Not knowing what to think, and not knowing whether he was laughing at me or with me over what I had experienced as a minor humiliation, I silently returned to my draft of the view below.

And silence reigned for some time between us, but I felt his reaction to each and every aspect of the landscape that slowly emerged from my pencil.

Now I freely admit that I was no more a landscape artist on 1st.January.1812. than I am now on 1st.January.1824. as I sit here in Sydney, ‘free by servitude’, feeling poorly, an imminent, ugly entry in the burial list at ugly Saint Philip’s Church, and perhaps writing this memorandum to expunge a lingering sense of guilt regarding that little black boy on Prospect Hill.

Maybe it’s because this first day of the year has reminded me of that first day of the year twelve years ago. Twelve years, perhaps the entire lifespan of that little boy when I first met him.

And maybe it’s because I now have children of my own with the fair Sarah Coates, our eldest, Mary, being born several years after I met the boy, and now four more daughters since, and Sarah expecting another that I will never see.

Yes, maybe I just want my daughters and that unknown child to know of my possible guilt for unwittingly betraying that young boy on Prospect Hill into a servitude that may have split his soul.

But why would I want my children to know such a thing?

Perhaps because what I may have accidentally caused that black boy to experience was the kind of servitude that I experienced.

There may be a salutary lesson for my children in this watershed memorandum of unwitting injustice from Prospect Hill.

That is my dying hope, at least, my posthumous prospect from Prospect Hill.

As I sat there on 1st.January.1812. like Prometheus tied to a stone awaiting yet another visitation from the hungry eagle sent by Zeus, the young boy became very agitated with the latest emergence from the tip of my pencil.

I had drawn the temporary prayer hut as it sat on the neighbouring high place slightly below us, and adjacent to the drawn hut, but some artistic yards away, I had drawn another of those mysterious circles of stones in unreal emulation of its very real and presumably permanent presence near the real hut.

Now the real prayer hut was plain enough, being both temporary and unsightly in nature, and I drew it with smoke coming from its chimney, even though such smoke only emerged on Sundays, and this was a Wednesday, and, at first, I thought that this smoke in the sketch that was not really there in the living of this moment had upset the boy’s sensibilities.

But I was wrong.

It was not the smoke.

It was my drawing of the second circle of stones below us that was the cause of the boy’s agitation.

He grabbed the pencil from my hand, yabbering in his own tongue, and struck out the circle of stones from my sketch as though he were Zeus himself commanding thunderbolts from Mount Olympus, and he left a grey, angry rectangle over where the circle of stones had once sat on the page.

And then he did a curious thing.

I have often wondered about it.

Was he a seer like Fionn?

Had this young boy eaten from the Salmon of Knowledge?

He drew a vertical aspect from the corner of his grey, angry rectangle, and the resultant geometrical confluence over the original circle looked for all the world like a grand church.

And was not a grand white church with such a steeple erected on that very spot near that very circle of stones in 1817 under the all-seeing eyes of an Irish commandant from Cork during the last year of my servitude in Newcastle?

And was there not talk of a lost Druid stone circle in Cork?

It still gives me a shiver to think of it, and I have to remind myself yet again that I am an Irishman of my time.

I am no Druid.

Or am I?

How could young Wepohng have known about that future Christ Church in Newcastle?

Was there some mystical stone connection between these local blacks and the ancient Druids in Ireland?

And years later, the young boy that was now a man, told me that the eaglehawks had placed those circles of stones on the high places in Newcastle, and I then truly felt like Prometheus unbound. ‘Free by servitude’ indeed!

But, at that moment of his furious scribbling on 1st.January.1812., I was still bound to that stone on Prospect Hill.

And I could still sense the next approach of the eagle that was eternally hungry for my regenerating liver.

Skottowe had been right about Prospect Hill.

This elevation offered the best prospect for the proposed sketches.

Lieutenant Thomas Skottowe of the 73rd (Highland) Regiment of Foot, the then recently appointed commandant of the Newcastle penal settlement, was that rare creature in my experience, an Englishman who was not a bastard.

And Skottowe and I shared certain artistic sensibilities with respect to natural history.

As a consequence of this sharing, Scottowe took me under his wing, and thus my servitude in Newcastle consisted of sketching and painting rather than hewing coal, lime burning or felling and fetching cedar.

I was more at home with natural history illustration in accord with my training, but first I had to satisfy Lieutenant Scottowe’s need for these two adjoining sketches for a planned publication by Absolom West.

Easier said than done, when I was more comfortable sketching insects, but I had decided that one sketch would capture the Newcastle settlement itself while its adjoining companion would capture the estuary of Hunter’s River.

At this early stage, I was attempting to capture aspects of both planned sketches on the one page within one draft sketch, not in the manner of a miniaturist, but more in the manner of one who must use his allotment of precious paper sparingly.

I had just finished the island that they call Nobby’s against a backdrop of the coast right up to Point Stephen when the boy intervened again.

‘Me,’ he said, reaching for my pencil.

And I watched in awe as he added a good likeness of the Lady Nelson rounding Nobby’s, and then he added carefully positioned columns of smoke on the opposing peninsula and the hinterland, though no such smoke was visible that day.

I have often wondered whether those sketched columns of smoke were secret blackfella business rendered by the boy, perhaps symbolically claiming the landscape as blackfella land much as the English had symbolically claimed it as English land via the Union Jack near Government House.

I recall glancing down to my right towards Government House and doing a draft rendering of its architectural façade along with its symbolic flagstaff, once the boy had returned my pencil.

And I recall that the sky in Newcastle was as blue as blue on that 1st.January.1812. Wednesday, and the light that I experienced on Prospect Hill was of a quality that I had never experienced in Ireland.

But it was not the light that had spooked me.

It was the boy’s sketch of the ship.

How did he know what the Lady Nelson looked like in such fine detail?

And did the seer within him know that the Lady Nelson would arrive in Newcastle within the next few days?

Was this some form of blackfella magic akin to the Druids at home in Ireland?

I shivered at that moment on Prospect Hill, and, despite the blue sky and humid heat, I added a layer of clouds to the horizon of my draft sketch.

I did hope and pray that the rain of Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England would not fall from those clouds and extinguish the columns of smoke below.

I felt an affinity with the plight of these local blacks.

And yet, despite that feeling of affinity, that night I told Skottowe of my meeting with the boy.

Why did I feel the need to do that?

Was I trying to impress the Lieutenant, or had this convict hell called Newcastle brought out the devil in me?

The gift of the gab on this occasion was my curse, the source of my ongoing feeling of guilt, and my subservient Irish need to impress my English master served only to depress me.

I showed Skottowe the draft sketch, and I showed him the additions made by the young black boy, the scribbled grey outline of a grand church, H. Majesty’s Brig Lady Nelson rounding Nobby’s Island and the columns of smoke.

And I told Skottowe of the boy’s naïve interest in the English language and his attempts to get me to speak like a blackfella.

And I showed him the bearded lizard as evidence of those linguistic aspirations.

The Lieutenant was impressed, and he advised me, in the whispered reverence of an unlikely confidant, that he would tell Governor Macquarie of the boy’s existence when His Excellency arrived in Newcastle within the next few days, if the winds were in Lady Nelson’s favour.

And, regrettably, the winds were in her favour eventually, ill winds for the boy and me.

‘Browne,’ Skottowe said, ‘you’re a good man. His Excellency may find a place for your black boy at the barracks in Sydney, for the boy’s talents and inclinations, so ably reported by you, Browne, could prove valuable for the colony.’

‘But he belongs here, Lieutenant,’ I nervously stated. ‘These blacks are like cats, sir, very territorial.’

‘Nonsense, Browne, and how could you possibly know?’ Skottowe observed. ‘You’ve only been in the colony since July, and in Newcastle barely three months.’

And it was true, but I was beginning to worry for the boy’s possible fate, and to feel the first inklings of guilt for my role in his probable servitude.

‘Now, Browne,’ Skottowe said. ‘The boy’s rendering of Lady Nelson is suggestive.’

‘How so, sir?’ I asked.

‘I think you should put more ships and boats in the final sketches to give the harbour a busy circumstance, even though it be quiet at the moment.’

‘Yes, sir,’ I said.

‘And you have presented the coast well, Browne,’ Scottowe continued, ‘but I think a cliff face should be included, even though such may not be seen from Prospect Hill … use your talent for forgery, man!’

‘Yes, sir,’ I said.

‘And I like the boy’s idea of columns of smoke, but balance them in some way, perhaps cooking fires with blacks in the foreground, and I want foliage in the foreground too.’

‘Yes, sir,’ I said.

‘And I don’t mind a hut with a smoking chimney, but not that ugly, temporary prayer hut … get rid of it, Browne, perhaps place a hut further down the slope slightly, because there surely will be one there prior to publication.’

‘Yes, sir,’ I said.

‘We need to think ahead, Browne. Perhaps a few more structures in the settlement itself for good measure, and I shall point out to His Excellency the boy’s placement of a grand church, a great spot for such a crowning edifice of prayer.’

‘Did you want me to include a cathedral, then, Lieutenant, perhaps in the final estuary sketch?’ I suggested. ‘There surely will be one there eventually …’

‘Now, let’s not get ahead of ourselves, Browne.’

‘No, sir.’

‘And His Excellency the Governor will want the settlement to be of such an ordered and tidy appearance, Browne, that the King could mistake it for an idyllic village in England, if His Majesty should ever do us the honour of viewing your sketch.’

‘Yes, sir,’ I said.

It was strange saying sir, me being a man in the shade of forty and Lieutenant Skottowe being just twenty-five. And our Staffordshire and Dublin accents were like ill-matched duelling pistols, but we were a matched pair that night as we finally put the draft landscape aside and went on to discuss under lamplight our shared vision of a natural history folio that would capture what was unique and beautiful in this otherwise unoriginal and ugly settlement.

I have wondered ever since Christ Church was built by order of His Excellency the Governor in 1817 whether the young black boy’s scribbling on my draft sketch had suggested the church with a steeple and the actual site of its construction in a case of life imitating art.

Could a seer actually inspire the construction of what he had foreseen?

Young Wepohng did seem to have as much to teach us as we might ever teach him.

Years later, when I met the boy who was now a man, he was called Magill after a Captain John Maunder Gill of the 46th Regiment who had taken charge of him at the military barracks in Sydney.

And he remembered me, just as I remembered him.

‘Liz … ard!’ he grinned.

His English was much improved, now that he was a man of perhaps nineteen or twenty years, and he still slowly articulated each syllable in the manner of a teacher.

He seemed happy, and he posed for me in full corroboree style, and, as I was painting him, he said: ‘We draw each other!’

When I looked at him blankly, he grinned, and he made a pouting face, poking out his tongue in the manner of a lizard, and he pulled on his beard as a reminder of our meeting on Prospect Hill seven years before when he had affixed a rendering of my rather fulsome beard onto the lizard’s face in my quick reptilian sketch.

‘You liz … ard!’ he said, laughing and laughing. ‘Coa … tung … ull … e!’

‘We have drawn each other,’ I agreed, grinning like an innocent.

But I still felt guilt.

Had I unwittingly condemned him to a grey servitude that was neither black nor white?

If I had not told Skottowe …

And then Wepohng, known as Magill, perhaps reading my thoughts, or perhaps knowing my thoughts in advance in the manner of a seer, said: ‘Blackfellas and whitefellas, we serve each other, we draw each other, we kill each other.’

And they were the last words that he ever spoke to me.

And then he frowned as though these last words were his final prophecy.

And then he smiled as though granting me absolution.

But I still felt guilt, and maybe that is why I have done my best to create a visual record of the blacks of this land, using stencils to enable a multitude of copies to be made, and the copies are most popular, and they do sell well.

I have portrayed the blacks of this land as shaded, silhouette figures, much as Wepohng had shaded that circle of stones in the form of a grand church at the moment of our communion.

Copyright Paul F Walsh 2022

Communion is a work of fiction inspired by a sense of reality

Paul F Walsh thanks Susan Harvey and Gionni Di Gravio OAM for research and editorial advice