Return to Yallarwah

Paul F Walsh

‘By February next year, it will all be here: Yallarwah Place, Yallarwah Bicentenary Walk and Yallarwah Circle of Reflection. And every person who looks upon this memorial over the next one hundred years will know. They will know that we built it with love in our hearts and the power of unity and tolerance in our hands. Could we leave them with a finer legacy than that?’

Paul F Walsh, Groundbreaking Ceremony, January 30 1998

I return like a boomerang.

But to whose hand am I returning?

I study the bronze hands at the front of the Yallarwah Place building.

The hand of Robert Smith, a humble man. He was my friend and comrade. When his black dreaming of an accommodation centre for the relatives of Aboriginal patients met my white Novocastrian Tales dreaming Yallarwah Place became a reality.

The hand of Andrew Refshauge, Deputy Premier, Minister for Health and Minister for Aboriginal Affairs. It was Andrew who declared the entire Yallarwah site to be a BICENTENARY MEMORIAL for the PEOPLE OF THE HUNTER REGION.

The Yallarwah Bicentenary Memorial is believed to be the first united and inclusive Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal memorial in Australia.

The memorial is inclusive in terms of its text, symbolism and manner of construction.

But this memorial is suffering from a loss of memory.

I note that the two mighty gum trees that once guarded the entrance to Yallarwah are now sad stumps.

‘There is a black and white dream that the bushland memorial at Yallarwah will become a communal rest area for all users of John Hunter Hospital; a special place to escape the stress and heartbreak that may accompany the illness of a loved one.’

Paul F Walsh, Black and White Dreaming, circa 2001

I study the hands of Gough Whitlam. Both hands. Very Gough. His right hand poured soil into the right hand of Vincent Lingiari.

I move beyond these bronze guardians to enter the building, which was designed by architect Peter McMullen in the form of an eagle-hawk astride a flying boomerang.

What am I to make of Lindon Dargin’s foyer artwork of a black spirit embracing a white spirit now being hidden under generic flooring?

I glance upward.

A low false ceiling is now blocking the view to the eagle-hawk’s head thus transforming what was an open foyer with a vaulted ceiling into a claustrophobic space.

This space was once flooded with natural light from the high windows that formed the eagle-hawk’s eyes.

I return my gaze to the foyer and beyond.

The original ochre-inspired palette of the building as a welcoming home away from home for Aboriginal people has been replaced by a predominant whiteness.

The white walls do feature Aboriginal artworks, but all artistic references to the reconciliation meaning of the Yallarwah Bicentenary Memorial and its connection to Novocastrian Tales and the massive YES support of the Hunter Region and beyond have been removed.

Ray Kelly, Susan Harvey and I take it all in, and I sense the genuine empathy of our three Hunter New England Health companions.

I leave the foyer to enter the courtyard.

The courtyard is covered in filth.

The mural wall is covered in filth.

The beautiful Aboriginal mosaics set into the pavers are now framed with filth.

I glance upward.

The eagle-hawk has been architecturally blinded.

I leave the courtyard via a set of broken stairs.

A well-intentioned but erroneous sign greets me.

I approach Yallarwah Bicentenary Walk which embodies the dual symbolism of the Rainbow Serpent and the Hunter River.

This stone-lined serpent is the sort of healing trail where I could meet my younger self walking towards me.

I immediately note that the once verdant bushland is degraded, and most of the Currawong Project tree plantings have died.

I plant this tree in the spirit of

the currawong,

black feather white feather

lifting me.

I plant this tree to call upon

all Australians

to replant a

shared future together.

The Currawong Project trees planted by Aboriginal leaders with Governor-General Sir William Deane, Governor Marie Bashir, Premier Bob Carr et al are no longer living in this forgotten memorial landscape.

I pass another Vlase Nikoleski hand plaque on the Rainbow Serpent trail bearing the legend:

Heart of our nation

Reconciliation

Where is our heart? I wonder, as I note that the Rainbow Serpent is eroded and rutted to the point of being dangerous in some sections of the trail. I recall how Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal volunteers fashioned this serpent from stone and dirt and heart.

The outdoor furniture is on its last legs with one piece propped up on a sewage fixture.

As I approach the dilapidated tables on their stone-lined viewing platforms, it becomes apparent that they now have a view of the evolving new road rather than a vista of nurturing bushland.

I hear a kookaburra laugh from my past. And I feel like laughing hysterically. Where has our collective sense of respect gone?

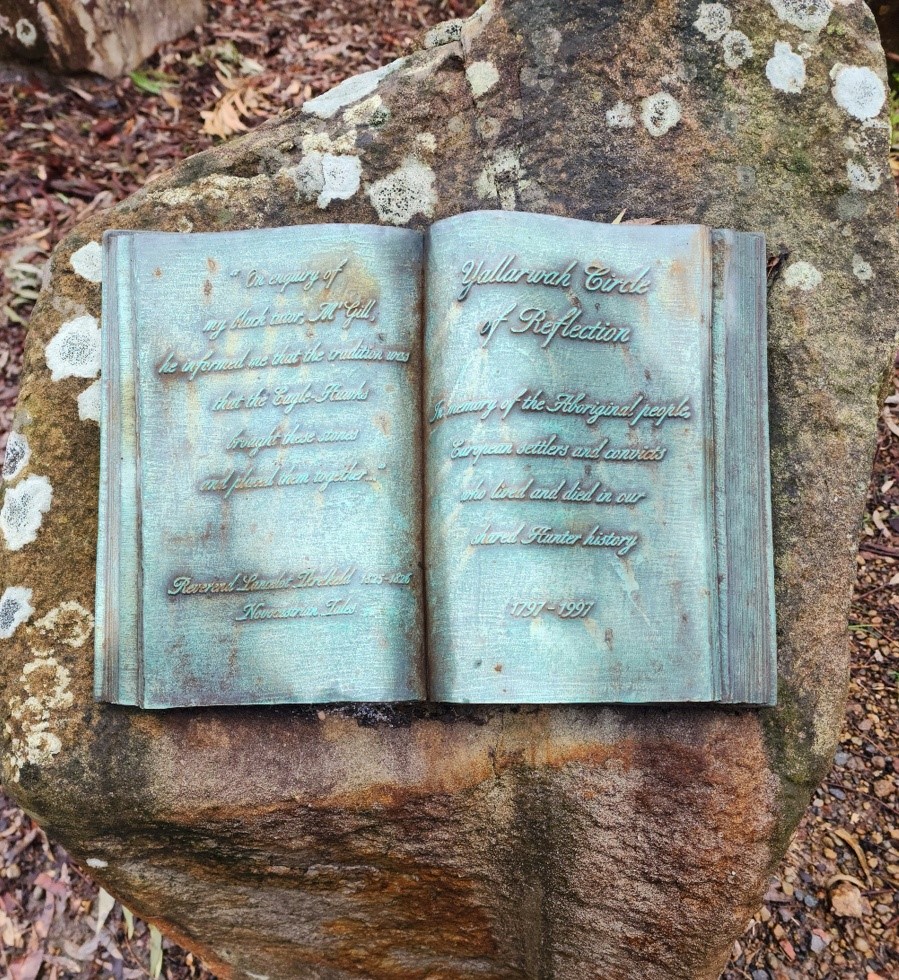

I approach Yallarwah Circle of Reflection which embodies the dual symbolism of the Rainbow Serpent’s Head and Newcastle Harbour.

I note the ugly impact of poor drainage, joggers and off-road bikes on this circle of stones, a circle of stones that was inspired by a conversation between Biraban and the Reverend Lancelot Threlkeld.

I ascend the stone steps with a descending stone in my heart, but there is still an eerie sense here, a sense of timelessness or time standing still.

The six large red gum trees still define Yallarwah Circle of Reflection, and the seven large stones are still aligned within the Serpent’s Head just as Ray Kelly directed almost twenty-five years ago, and the bronze book still sits on the central stone and conveys its inclusive memorial message.

But the evolving new road is omnipresent. Very close, and visually and noisily in likely future conflict with the entire concept of quiet reflection.

The Serpent’s Head is compromised, and yet we all agree standing there around the bronze book under the canopy of the six red gum trees that there is still an undeniable beauty here.

Uncle Bob Smith mingled the soils within the Serpent’s Head as a sign that all people were welcome at this place of healing.

But this place of healing now requires healing.

This wounded and neglected country is speaking to us.

The land here is calling for our YES.

The mingled soils here are calling for our YES.

How can we say NO?

Reconciliation magic and history happened here twenty-five years ago, and it now happens here again.

The Hunter New England Health team take a leading YES role in aspirations to transform the apparent negative of neglect and degradation into a positive.

Plans are mooted to improve, restore and repair the entire Yallarwah Bicentenary Memorial site.

There are discussions concerning a proposed 25th birthday tree-planting ceremony that could be held on February 19 2024.

There are hopes expressed that this 25th birthday ceremony will inspire an annual Yallarwah event to bring life and memory to this site of black and white dreaming.

There is a feeling that the torch is being passed to a new generation as we listen to the empathetic YES from our Hunter New England Health companions. I feel it. And I think that Ray and Susan are feeling it too.

There is a suggestion that the Serpent’s Head will be screened from the new road by tree plantings and other visual and sound buffer measures.

I feel an excitement for a future that my body will not see.

I will not see the new trees fully grown, but my hovering spirit will know of their growth.

And in that moment, I realise:

I have not returned to Yallarwah.

NO!

Yallarwah has returned to me.

YES!

And there is a higher truth:

I never left …

and I never will.

‘A large group of tree planters recently stood for a minute’s silence in memory of Uncle Bob Smith. We stood at the Serpent’s Head within the Yallarwah Memorial in the bushland at John Hunter Hospital. We stood to welcome the spirit of Uncle Bob Smith into a site of black and white dreaming. And just as we stood, a gust of wind swirled around the Serpent’s Head and caused the leaves in the canopy above to chatter. It was a special moment for a special man.’

Paul F Walsh, Black and White Dreaming, circa 2001

Copyright Paul F Walsh 2023